Netflix streams "Joy" about the birth of IVF

A medical revolution viewed through Jean Purdy's eyes

People who know or care about this story have waited for years for it to appear on the big screen. It means so much to the families of 12 million IVF babies and counting. The movie premiered in London last month and is now streaming. It has multiple reviews, including the Guardian, New York Times, Time magazine, et cetera.

I was eager to see if it matches the real-life actors and scenes I knew as a graduate student and research fellow in Cambridge in the 1970s. Pathé contracted screenwriters, Jack Thorne and his wife, Rachel, which raised my hopes because they are IVF parents. I liked the movie enough to watch it a second time in 24 hours.

It is based on the true story of a British trio pursuing a goal people thought impossible or immoral. Their stormy endeavor was so packed with setbacks and emotional surges that it didn’t need extra freight, but the writers couldn’t resist adding spin. I muttered to my wife whenever a scene contradicted what I knew or remembered, but then I corrected myself. This is a drama based on events, not a documentary history.

It begins in 1968 at picturesque Cambridge University. Before the breakthrough with a baby a decade ahead, the team has a dogged and lonely struggle which we follow with Jean Purdy, played by the talented young New Zealander Thomasin McKenzie. Bill Nighy fills a vivid role for the upper-crust obstetrician-gynecologist, Patrick Steptoe. James Norton plays the Bob Edwards part who had the driving brain behind the project, but the script fails to flesh out his inspirational brilliance.

I am glad the childless women who contacted them are not shadowy figures. They called themselves the Ovum Club and were equally heroic. Their struggles and solidarity can move eyes to tears. The experimental treatment failed them again and again, but the knowledge gained in disappointments through trial-and-error honed a technology that eventually benefitted others right up to this day. The very first pregnancy raised everyone’s hopes to the stratosphere until found lodged ectopically in the fallopian tube and had to be terminated. We see no more of the patient Rachel, who tried several more IVF cycles but never had a child. You don’t have to be a hopeful parent to feel her pain.

Patients came from across the country and beyond, including all economic classes, because they didn’t pay for treatment. How different in America today, where treatment is often too costly for the poor. Lesley and John Brown are perfectly cast as the first successful couple. They came from a working-class home, not so different from Jean and Bob’s. In the movie, when Patrick aspirates the single mature egg from Lesley’s ovary, Vaughn Williams’s Lark Ascending plays on a vinyl LP in the background to raise our emotions, despite already knowing this one will conceive their daughter Louise Joy Brown.

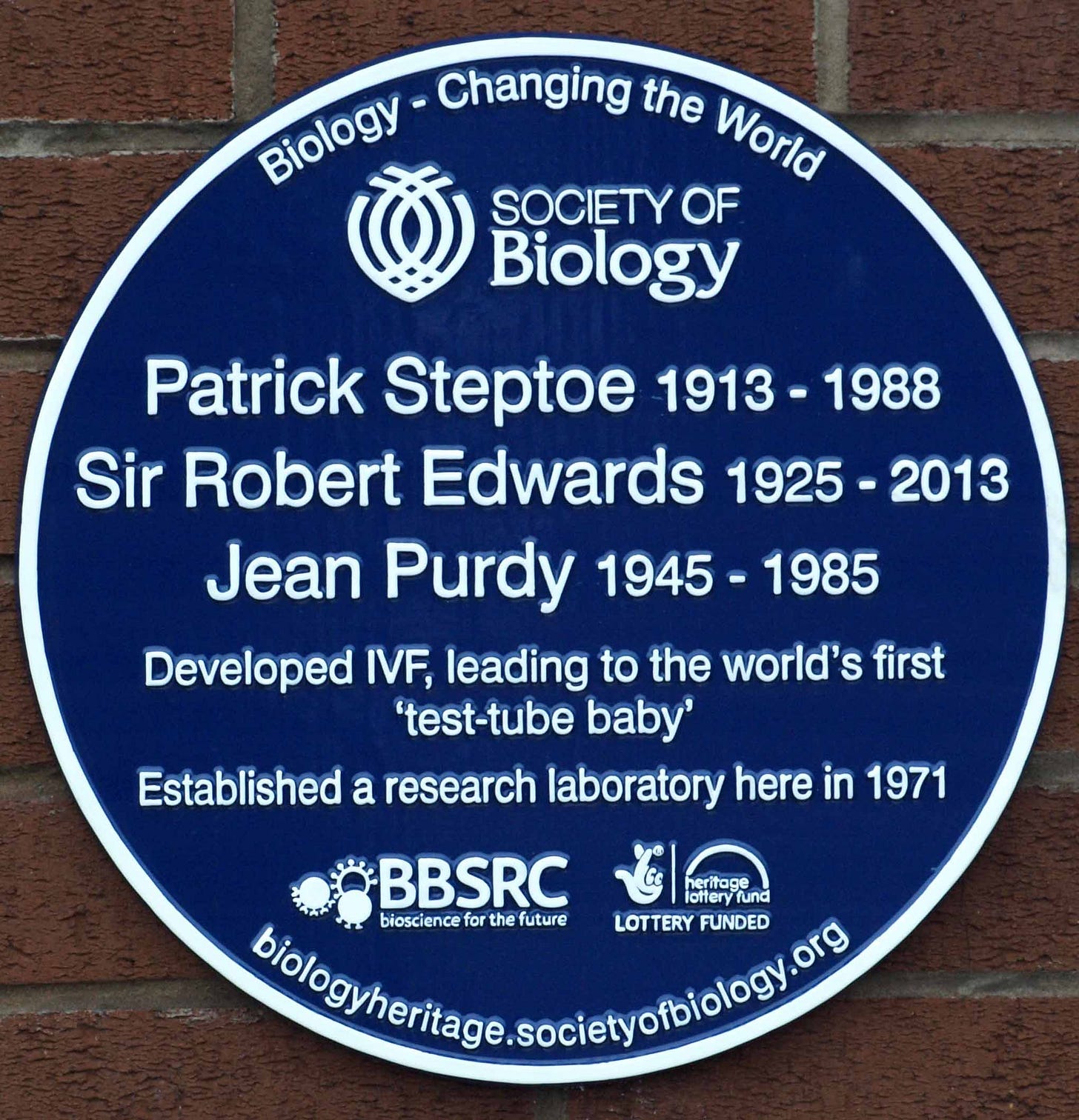

I am also relieved the writers tell the story through Jean, not only because women carry much the greater burden of treatment, but she received too little credit in the shadow of two older professional men with A-type personalities. Trained as a nurse and never earning a science degree, she started knowing nothing about human embryology, yet she became the world’s first clinical embryologist. Bob urged hospital managers to include her name on a plaque commemorating their achievement, but he never prevailed. It didn’t happen until 2015 after he had died when the Society of Biology honored her.

Jean became so much more than a technician when she switched from nursing at age 23 to work for Bob in the lab. She took scrupulous care, constantly checked materials and equipment, recorded data, collected specimens, monitored embryos in culture, and counseled patients. Bob acknowledged the talent he had unwittingly recruited by using her as a wise sounding board for testing radical ideas. When she took leave to care for her dying mother in 1974, the program was suspended because it depended on her. On her return, she had to overcome Bob’s discouragement with the lack of success for them to restart.

I was ever a researcher and educator and never a clinical practitioner like my wife, Lucinda. I regard her as Jean’s doppelgänger as the embryologist for the first successful American IVF program. They had awesome skills and ethics, caring for tiny charges in Petri dishes they knew meant the world to someone. To be at the top of this profession, she told me you have to be slightly OCD until IVF labs become fully automated.

People familiar with modern clinical and research labs might think the depiction of Kershaw’s hospital is too primitive for belief, but I assure them it is rendered fairly accurately. They had no government funds, mostly operating on a shoestring budget until an American woman made a generous donation. Knowledge of human embryology was equally poor in those days, so they had to develop methods from scratch because they only had rodents to go on, which have a different physiology (monkeys came on stream much later).

If you grew up with IVF as the standard of care for infertility, you might doubt the hostility portrayed in the movie from senior scientists and doctors, politicians and church leaders. I remember the press calling Bob Dr. Frankenstein and accusing the team of Playing God. It wasn’t funny when their family members and neighbors read the newspapers. The Yorkshireman gave his opponents as much slagging off as he got and provided as much cover for his colleagues as he could. Their foes never accepted total defeat and are reawakening at this moment in America’s moral wars over reproduction.

Jean grew up a member of the Christian Union but never paraded her faith. I suspect the writers invented a conflict with her pious mother and church, though I can’t prove it. Religious opposition was not monolithic. Some Anglican priests took the side of IVF, and many Roman Catholics have opted for treatment despite implacable resistance from the hierarchy.

Jean had an acute sense of social justice, and like her boss, she sympathized with underdogs. As an instance of that sensibility, I overheard her hammering against apartheid in a conversation with a South African, and so I can imagine her defending women’s rights. But after work, she could be funny and helpful to graduate students who got into foolish laboratory scrapes (like me).

She didn’t reveal her private life, or whatever time was left after work for recreation, though she couldn’t hide the abdominal pain that occasionally sent her to the emergency room in agony. I was puzzled why the movie never showed symptoms of the endometriosis she admits having. The writers were tempted to present this disease for its poignancy when a woman who is permanently sterile commits her life to helping others whose infertility is curable. I am sure Jean would never have wanted to appear as a victim of a cruel disease. She is shown to disappoint her mother’s hopes of becoming a grandmother by declaring she had unprotected sexual intercourse for years to prove her infertility. This scene irritated me because in all the years I knew her, she never went out on dates, too busy at work.

Since the story ends with the first baby in 1978, viewers miss the tragedy of her death from cancer seven years later at age 39. During her final years, she helped several hundred babies into existence, but before she could witness IVF blossoming all over the world. The two men quickly elevated to medical celebrities. When Patrick died, Bob became the lone survivor for 25 years, but not until near the end did dignitaries get around to acclaim him with a Nobel Prize and knighthood.

Jean was robbed of recognition by an untimely death, her gender, and by not having the qualifications of a doctor or scientist. There have been Johnny-come-lately biologists who don’t credit her as the world’s first clinical embryologist because she was uncredentialed although supremely experienced. “She was just a tech.” She had a special role, and that’s true for every pioneer compared to workers in a mature field today. That role has grown in our estimation since two former colleagues published extracts of her lab records in the Oldham Notebooks.

When the final member of the trio died in 2013, I knew they would fade from public consciousness. I doubt if their names are known to many patients or even some junior staff in reproductive medicine. IVF had already become ordinary and mostly uncontroversial. We could have done more and sooner to bring her to public notice. Perhaps this movie will blaze her reputation.

I wrote on my blog a posthumous epistle to her titled Dear Jean to bring her up to date with progress in IVF since her passing. I don’t apologize for that sounding weird! When I returned to Cambridge that year, I took the footpath to Grantchester village where she was buried.

I found her grave in a corner of the parish churchyard where she lay beside her mother. The lettering on the headstone was peeling off and omitted her achievements. A ragged bunch of plastic flowers were the only sign that anyone cared. A few years later, the memorial would have joined anonymous stones leaning on the lawn.

We raised money for a grand new memorial inscribed with a tribute to her place in medical history. Louise Brown unveiled it in 2018 in the presence of the media. If you visit Cambridge, maybe you will take a short pilgrimage to that peaceful place, but if not you can go to the Grantchester Church website, which has an account of her life on a list of “interesting people” buried on its grounds (the church for the TV detective series Grantchester).

Images: Jean and Bob reclining on the lawn during a party for patients and their children at Bourn Hall Clinic (c. 1983-4). Blue plaque at the Royal Oldham Hospital (the former Oldham and District Hospital)

Further reading: I published a biography of Jean in a journal in 2017 that the editors permitted me to include in full on this Substack (May 2024).

A Matter of Life by Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe. ASIN: B00770VT60. 1980.

Let There Be Life. An Intimate Portrait of Robert Edwards and his IVF Revolution by Roger Gosden. 2019.

Next Post: A cold look at egg freezing

Thank you Roger for alerting us to this film. I really enjoyed seeing the story of the original pioneers of IVF brought to life, and remember meeting Bob Edwards in his later years. He was by then, a bit different to the young man in ‘Joy’! So nice too that Jean Purdy’s role was really brought to the fore.

Seeing the portrayal of the labs made me chuckle. The difference between that very early equipment and what was in use in embryology labs in the late 80s was not so vast compared to how much labs have changed over the past 30 years - from making our own culture media and incubating in gassed dessicator jars, to buying in optimised media and AI-based incubators today…

How things have progressed from those early pioneering days, and how much we owe them for their grit and determination…

Hi Roger, I'm so glad I found your substack, you are a beautiful writer and it's lovely to hear you talk so fondly of your memories with Jean Purdy.

I hope you don't mind but I have quoted you in a substack I've written, also reviewing the film 'Joy' which you can find here: https://open.substack.com/pub/rebeccacoxon/p/searching-for-the-real-jean-purdy?r=6iod5&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true

I hope it does justice to Jean. She sounds like a wonderful woman and I'm so grateful for her tireless work and dedication all those years ago.