This is a short biography giving tribute to Jean’s role in developing IVF. Originally published in 2017, Taylor & Francis permitted me to post it on this platform.

Summary: Jean Purdy is almost forgotten as one of the British trio that introduced clinical IVF to the world. An unlikely pioneer, she qualified as a nurse but through indefatigable effort and unstinting loyalty to a programme that faced bitter opposition she became the clinical embryologist for the first IVF baby. In 1980, she helped to launch fertility services as the Technical Director at Bourn Hall Clinic, near Cambridge. Although Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe credited her role in research and clinical care, a premature death in 1985 at age 39 robbed her of the reward of witnessing the blossoming of assisted reproductive technologies for patients around the world.

In a plenary lecture at Marrakesh celebrating the 20th anniversary of clinical IVF in 1998, Robert Edwards gave a hearty tribute to Jean Purdy. I remember him saying ‘There were three original pioneers in IVF and not just two’. That he felt necessary to endorse her place in history to an audience of specialists was a sign she had already been forgotten 13 years after her premature death from malignant melanoma. She is much less visible now, almost 20 years later, and neither he nor Patrick Steptoe is around to remind us.

Jean was pivotal in the team that negotiated revolutionary technology through years of controversy to launch an effective fertility therapy throughout the world. She never sought the limelight, not so much because she lacked the qualifications or charisma of her male colleagues, but because she was happier counselling patients in the background and caring for their embryos while Bob and Patrick were the public faces of the programme. Bob struggled for years with the hospital administration in Oldham to add her name posthumously to a plaque commemorating their joint achievements. Had she known about the push-back, she would never have been bitter or complained that honour ignored is honour denied. To Jean work is its own reward. Other women in science and medicine are belatedly receiving recognition, like the African American mathematicians at NASA featured in the movie and book Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly, but Jean Purdy’s life is still rather hidden.

Jean (Jeannie to her friends) was born in Cambridge in 1945 to George and Gladys Purdy, two years after her brother. George was a technician in the University’s Chemistry Department while his wife was a homemaker and mother. Although not a prosperous or auspicious start to life, she had the immense benefit of a happy and loving family. She was a popular and conscientious student at high school between 1956 and 1963 where she became a prefect, joined sports teams, and played violin in the orchestra. In a final school report, her teacher wrote: ‘Jean’s pleasant personality and ability to get on with other people make her very suitable for the (nursing) profession which she has chosen to follow.’ They were prescient words.

After training as a nurse at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, she moved to Southampton to work at the Chest Hospital. Becoming homesick, she transferred to the Papworth Hospital in her home county where open-heart surgeries and heart transplants were pioneered in Britain after 1979. In 1968, she took a position as research assistant to Robert Edwards at the Physiological Laboratory in Cambridge. It was an unlikely move for a young nurse aged only 23 with limited experience in laboratory work. At first, Bob didn’t know his luck, and she didn’t realize the move would shape the rest of her life.

He had recently started to collaborate with Patrick Steptoe, the surgeon who introduced laparoscopy for gynaecology in the UK. This technique was vital for harvesting oocytes without major surgery. They wanted to bypass occluded Fallopian tubes for patients to conceive with IVF, which had only worked up to then in rabbits and rodents. A venture that began with modest goals would eventually push boundaries to ever more powerful technologies, for ‘only those who will risk going too far can find out how far one can go’ (T.S. Eliot, Preface to Transit to Venus (Poems by Harry Crosby), 1931). Knowledge of human embryology was paltry then. The technical hurdles were immense: how to collect ripened oocytes through keyhole surgery, develop culture conditions for fertilization and embryonic cleavage, distinguish healthy from abnormal embryos, and replace embryos in the uterus.

Bob put Jean in charge of the laboratory. She quickly earned so much respect from him that she became indispensable and a go-between for the pair of strong male personalities. The tiny team was separated by nearly 200 miles of what were then mostly non-motorway standard highways between Cambridge and Patrick’s medical practice in Oldham, Lancashire. Little did they know it would take ten years of striving and more than a hundred round trips to the north country before the birth of Louise Brown. Jean worked away from home for a week at a time, sometimes managing the lab alone when Bob had to return to Cambridge to teach undergraduates and supervise junior researchers like me.

The laboratory facilities at Dr. Kershaw’s Cottage Hospital (now a hospice) were extremely primitive even by the standards of the day with limited funding. But they had vision and determination, without which no great enterprise can succeed.

The lab was an 8 m2 windowless box room with barely enough space for two people to work. Crammed on a table under shelves for storing chemicals, they kept a weighing balance, a vessel of double-distilled water, a pH meter, and an osmometer for testing culture media. A binocular microscope rested inside a laminar flow hood occupying half the floor. Since gassed incubators were unavailable in those days, Jean cultured cells in a bell vacuum desiccator jar filled with 5% CO2 and warmed in an incubator. The inventory cost less than ₤10,000.

Bob only allowed Jean in the lab, apart from Dr. Joe Schulman who came on an American clinical science fellowship. A rarity in his profession in 1974, he anticipated the huge potential of IVF.

Jean’s role is clearer since Martin Johnson and Kay Elder analysed twenty-one laboratory notebooks in 2015. She ordered laboratory supplies, prepared culture media, helped to monitor gametes and embryos, and recorded data. Training as a nurse prepared her for sterile techniques and gave her a grounding in reproductive physiology and anatomy, although embryology hardly figured in the curriculum.

Patrick had an operating room next to the lab. To observe the customary territoriality of a surgical team, Jean did not become directly involved in oocyte retrievals. She conveyed fluids from them to Bob who took sole responsibility for searching cumulus-oocyte complexes and handling embryos. She did, however, help to design the first tool for vacuum aspiration, record embryo development, and check chromosome count in fixed specimens. When the programme switched from hormonal stimulation to single oocyte recovery in natural cycles, she rose every few hours in the night to rouse patients to collect urine specimens, testing them for LH surges with one of the first immunoassays.

Bob acknowledged her contributions with co-authorship of 26 academic publications, including three in Nature or Lancet. According to her obituary in The Times of London, thought to be written by him, she was the first person in the world to recognize and describe the formation of human blastocysts. Some years later, an American team isolated the first embryo stem cells from human blastocysts laying the foundations for new technologies in regenerative medicine.

He mentioned her role in his 1989 autobiography: ‘It was no longer just Patrick and me. We had become a threesome … (she was) the patient, indomitable helper without whom none of our work would have been possible …’ Joe Schulman recalled how she was ‘tremendously devoted to Bob and the IVF project’. In this triangular collaboration, Bob provided the inspiration, Patrick the application, and Jean the dedication. It became obvious that she was integral to the programme when they suspended it for months because she couldn’t travel during her mother’s final illness. Around that time, Bob was depressed by the toll of unsuccessful embryo replacement cycles and criticism from his profession. He considered giving up IVF research for a career in politics, but Jean persuaded him to keep going according to a rumour.

People who faintly knew her thought she was a quiet and unassuming woman, both are true, except she could roar at social injustices and criticism of the IVF team. It was an ugly time. They were accused of breaking moral boundaries by experimenting with embryos and discounting the risks of creating unhealthy children. But despite reproach from famous scientists and doctors, she didn’t feel any conflict with her Christian faith, regarding IVF as a calling to help couples have children that nature denied. If she ever harboured a dream of getting married and building a family of her own, there was never time for fulfillment. Instead, she gave all to an endeavour that looked bleak until a breakthrough in 1978 when the first IVF baby was delivered.

At that triumphal time, Patrick was forced by age to retire from his practice in Oldham. The National Health Service refused to support a publicly funded fertility service. The trio made urgent attempts to fund a private clinic near Cambridge where they could work together. During a two-year gap in clinical work, Bob wrote a monumental textbook of over 1,000 pages for which she made a huge contribution as a research assistant trawling journal articles in the city’s libraries. Releasing her occasionally to scout for new premises, she eventually found a Jacobean manor house for sale. It became the renowned Bourn Hall Clinic.

A few years after they opened a new clinic, the Hall hosted scientific workshops for specialists from around the world to share knowledge. I remember in November 1984 Jean drove us from the University Arms Hotel to a meeting at the Hall ten miles away. Only an unnatural pallor betrayed a dire diagnosis behind her welcoming smile and jokes. When her condition deteriorated, Bob arranged a bed for her in the Hall’s attic where she could still be a part of the team and receive visitors. Tim Appleton, a Cambridge physiologist who took holy orders and became the first fertility counsellor, spent a lot of time with her. She assured him she was luckier than other people who didn’t know how long they had left in life. The kind of fortitude she showed at work now carried her through illness until passing away in 1985 at age 39.

Jean was buried beside her mother and grandmother in Grantchester churchyard, a beauty spot outside Cambridge associated with the First World War poet Rupert Brooke. Her headstone gives no hint of a significant life, and the lettering is peeling. A bunch of plastic flowers was the only sign of care the last time the author visited that forlorn corner. History expects a fitting memorial, even for a subject who would never ask for one.

Jean’s life might seem tragic but in another sense it is enviable. She poured energy in a short span of years into an enterprise that gave meaning, something that eluded many people. It made a difference in other lives. Public acclaim is not needed when endeavour is no sacrifice and provides a private solace that is its own reward, as it was for the fictional heroine in George Eliot’s Middlemarch: ‘… that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who have lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.’

Do not look for Jean Purdy’s legacy in published papers or laboratory practices but at the 370 children conceived in Oldham and at Bourn Hall Clinic during her tenure and the joy that they and many others inspire.

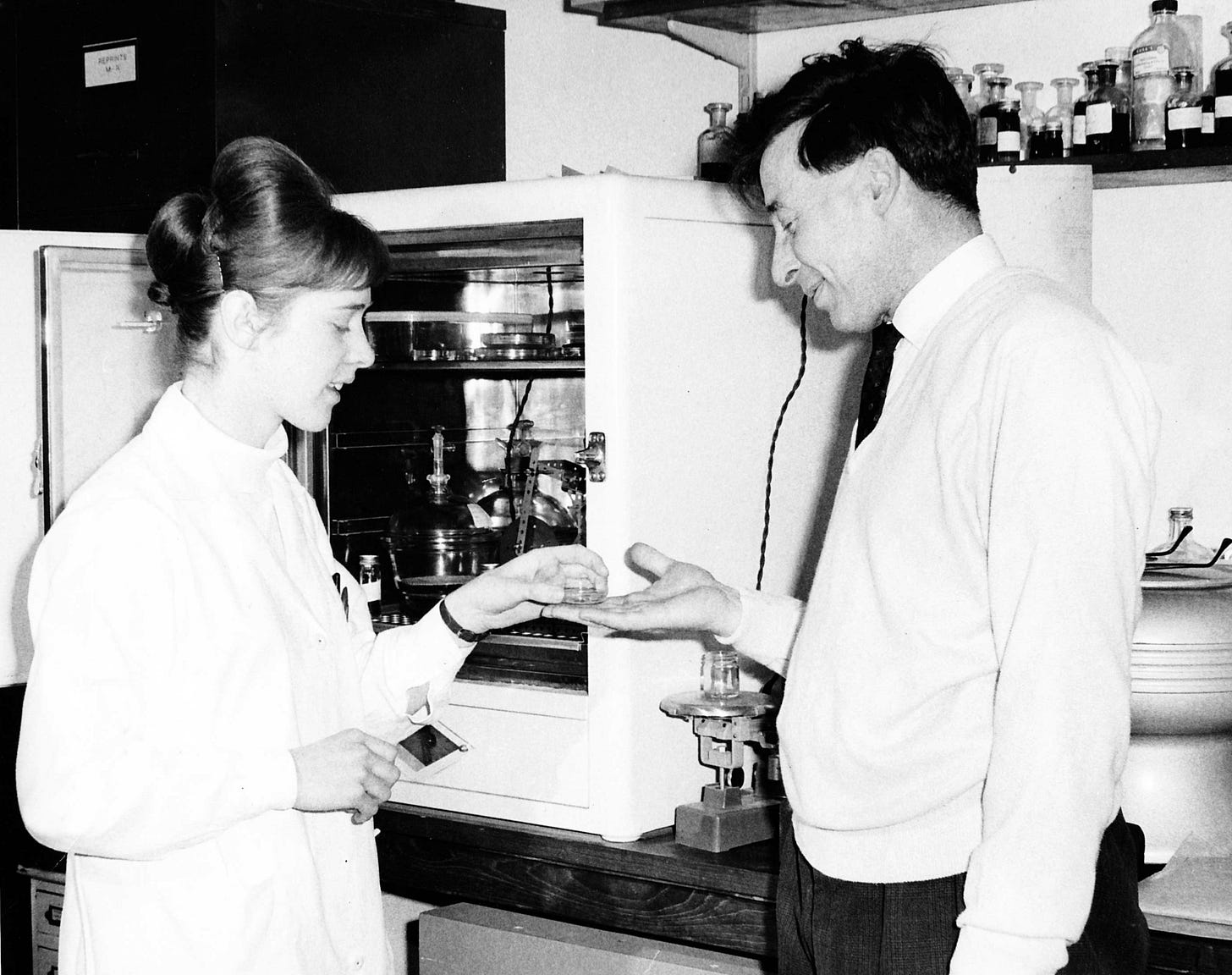

Illustrations: #1. Jean and Bob in the lab, circa 1970. #2. Jean’s new memorial in Grantchester.

Addendum: A year after I published this short biography in a British journal, we replaced Jean’s old headstone with a more durable one inscribed with tribute. The appeal for funding was supported by her friends, colleagues, the British Fertility Society, and the Association of Clinical Embryologists (UK). At the dedication in Grantchester churchyard on July 20, 2018, John Purdy (her brother) and Louise Brown spoke to the media about her life and work.

[This is an original manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis on 07 Sept 2017, available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14647273.2017.1351042. Permission to post on this website granted by the publisher]

You can read more about Jean in the author’s authorized biography of Bob Edwards: Let There Be Life: An Intimate Portrait of Robert Edwards and his IVF Revolution.

Next Post: Human Embryos: a personal issue (Ethics & Embryos part 1)

Thanks Roger for this biography. It is amazing to hear about Jean's contribution to those early days and to find out that she was the first person in observe a human blastocyst in vitro! When I began my career as a clinical embryologist in Sheffield (c1990), we used to make our in-house IVF media and supplement with 15% serum donated by our fertility nurses. We didn't have freezing technology back then and we kept embryos in culture to Day 5. I remember seeing human blastocysts develop for first time - truly amazing. I took a photo of one using a polaroid camera through the microscope eyepiece. I presented it on a poster at my first ESHRE meeting in 1993. The poster (made of sections of card, as we had no digital technology back then) was awarded a rosette, presumedly because few people had seen such a photo! Yet, to now know that Jean was the first embryologist to see a human blastocyst is humbling. She must have been so excited - and yet only able to share the news with Bob and Patrick!

What a wonderful person she was. Jean was ahead of her time and left a legacy of a lifetime. It is so sad she died so young but she left her mark on the world and now the threesome are United in time again. Her legacy lives on in the beautiful lives she helped bring into the world.🫶🩷🙋♀️