Fertility Treatment for the Demographic Transition

Can Assisted Reproductive Technologies soften the landing?

In the recent movie about the birth of IVF, a British doctor on a government panel scoffed at Edwards, Steptoe, and Purdy. I paraphrase him: “Dr. Edwards, why do you think your program deserves a research grant? Infertility treatment counteracts our urgent goal to control the population explosion.”

Never shy of challenging authority, Bob Edwards snapped back: “They are important and separate matters!”

The Medical Research Council turned down their application.

I heard the criticism on other occasions before the birth of Louise Brown. It defies the United Nations' right to build a family. Isn’t it unjust if we who have the liberty to reproduce willy-nilly deny the gift of children to others?

The skeptical doctor looks ludicrous today, like the emperor with no clothes. What was he thinking of? If the few dozen patients in the nascent IVF program were successful, they wouldn’t have a noticeable effect in a nation producing 800,000 babies every year. Government research into contraception never generated a major discovery, whereas the infertility team made a historic breakthrough with few patrons and paltry funds.

I doubt that pioneers or their Australian competitors realized they started a revolution that would conquer infertility to which our species is peculiarly prone. Help was coming for most problems, for men and women, for around the world, and created new types of family unit. What would critics from sixty years ago say now when twelve million people have been conceived by assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs)?

Babies are not only gifts to parents, but to society as well. In countries where celebration of individualism trumps community interests, the wider benefits of other people’s fertility are not acknowledged enough. This is the nub of my essay. It’s not another defense of treatments no longer considered controversial (well, almost true). I will argue that baby-making with IVF is demographically positive: it helps a softer landing for the global transition from high to low reproduction. But, first, I will rewind history before making a forecast.

The 1960s and ‘70s were not only turbulent times in politics but became mired in anxiety about overpopulation. Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb (1968) warned that teeming numbers would trigger an apocalypse in our lifetime from mass starvation, social unrest, and plundering natural resources. In the living world, species suffer an abrupt fall from exceeding their carrying capacity in the environment. The sociologist William Catton Jr. explained why we are exceptional in Overshoot (1980). We have defied biological gravity through our inventions, but a reckoning will come. If everyone enjoyed the same wealth and health as in the richest countries, we would have already overshot by consuming too much of the planet’s finite materials and energy.

These warnings so alarmed me and some of my peers that we zealously started careers in reproductive science and public health. With the single-mindedness of youth that is a blessing and its bane, we assumed that more contraception can save the Earth. National and international agencies funded research as never before or after, while industry churned out pills and devices. In the most populous countries, desperate policies coerced people into sterilization (India) and enforced a maximum of one child per family (China).

Although much has been learned and delivered through research, has it buckled the soaring curve of population growth? Not a bit! Population growth carries momentum from younger generations. People chafe at interference with a free act that brings children dear to our hearts. I say that as a parent. Climate science now holds a pole position once occupied by population. I don’t underestimate its importance or link to population, but will it or can it mitigate rising carbon dioxide and its effects? We can’t row back the dirty legacy of industrial history. To change course will require amending human behavior and picking our consciences more than clever science and technology.

I laugh at ironies in reproduction. Early in his career, Bob Edwards worked on a contraceptive vaccine until he walked away from controlling fertility to promoting it with ARTs. Other scientists and physicians made similar U-turns, myself included after a stint on the neurochemistry of reproduction. Scientists migrate to problems they think are soluble or urgently needed.

Bob was the first scientist I heard ridiculing the threat of overpopulation. I couldn’t believe my ears. We are overwhelming the globe, and family planning programs are as vital as ever. Each extra pair of feet leaves an impression on the Earth, albeit some far deeper than others. I came round to realize that population is a plural problem. David Attenborough expresses this as a challenge to citizens and society:

“… we can stop consuming so many resources, we can change our technology and we can reduce the growth of our population.”

The world population reached three billion in 1960. In fewer years than my lifetime, we added five billion more people. The population clock chimes another billion every 12-13 years because births exceed deaths by 130 million to 60 million. We hardly sense we entered a lower birth era until studying the data, and a future population collapse is too far over the horizon to be seen.

To be stable, a population needs 2.1 births per woman (reminiscent of the R value in the Covid pandemic). The number exceeds 2.0 because 1.06 boys are born for every girl, so when (1.06 + 1.0) is divided by 0.98 girls surviving to childbearing years, we get the memorable number 2.1. It isn’t like a hard constant in physics, being subject to survival rates and gender bias (from abortion), and, hence, higher in many developing countries.

We thought that birth rates would stay high until countries become prosperous, but that’s mistaken. They are falling in rich and poor nations alike, and sometimes precipitously. In an extreme case, the South Korean government declares the fall to 0.72 a national emergency. Other countries in the region follow suit, including China, which canceled its one-child policy in 2016. Two southern Indian states have reversed policy to encourage larger families. The reasons for low births are multiple: economics and housing costs, women’s education and employment, delayed marriages and finding acceptable partners. Many young Korean women don’t aspire to be mothers and homemakers like previous generations.

When the Black Death decimated Medieval Europe, institutions, hierarchies, and social norms crumbled. Tensions in England triggered the Peasants Revolt in 1381. The transition from high to low reproduction now unfolding will strain autocratic regimes and democracies. They will quake at public discontent despite trying to maintain living standards, public order, and welfare with too few young people for the elders born in a higher fertility generation.

A distorted age distribution from fewer births is a graver cause of concern now than overpopulation. A healthy distribution is pyramidal. It has a broad base from newborns with shrinking cohorts of older people above up to the sole survivor at the top. This profile will change to look like a Christmas tree with small branches near the bottom overshadowed by a broad canopy above. Who can say how far this narrowing from the base will go or how future generations will adapt?

In a scramble for pronatalist policies, governments are already offering more support to young families, including child daycare, maternity, and paternity leave, and tax benefits. However, they have only had minor impacts on birth rates, like the unlocked Chinese one-child policy. What other incentives can raise birth rates? Since women can’t be compelled women to have babies, can immigrants and/ or robots fill the gap of missing workers?

There is another partial solution for demography that shouldn’t raise doubts or hackles. While many people choose smaller families or stay childless, millions of others worldwide cannot have children. They don’t have access to fertility services and can’t afford them. A national investment can pay off demographically while fulfilling the hopes of people committed to parenting given the chance and able to raise fine citizens. Isn’t this a win-win?

Only half a million babies are now being conceived annually by IVF, although under 1.0% of all births. That must grow. The impact will be far greater than the sum of their births because many will become parents and grandparents as roots of family trees. The number who owe their lives to IVF, either directly or indirectly as descendants, will grow geometrically. I wondered how much by the end of the century.

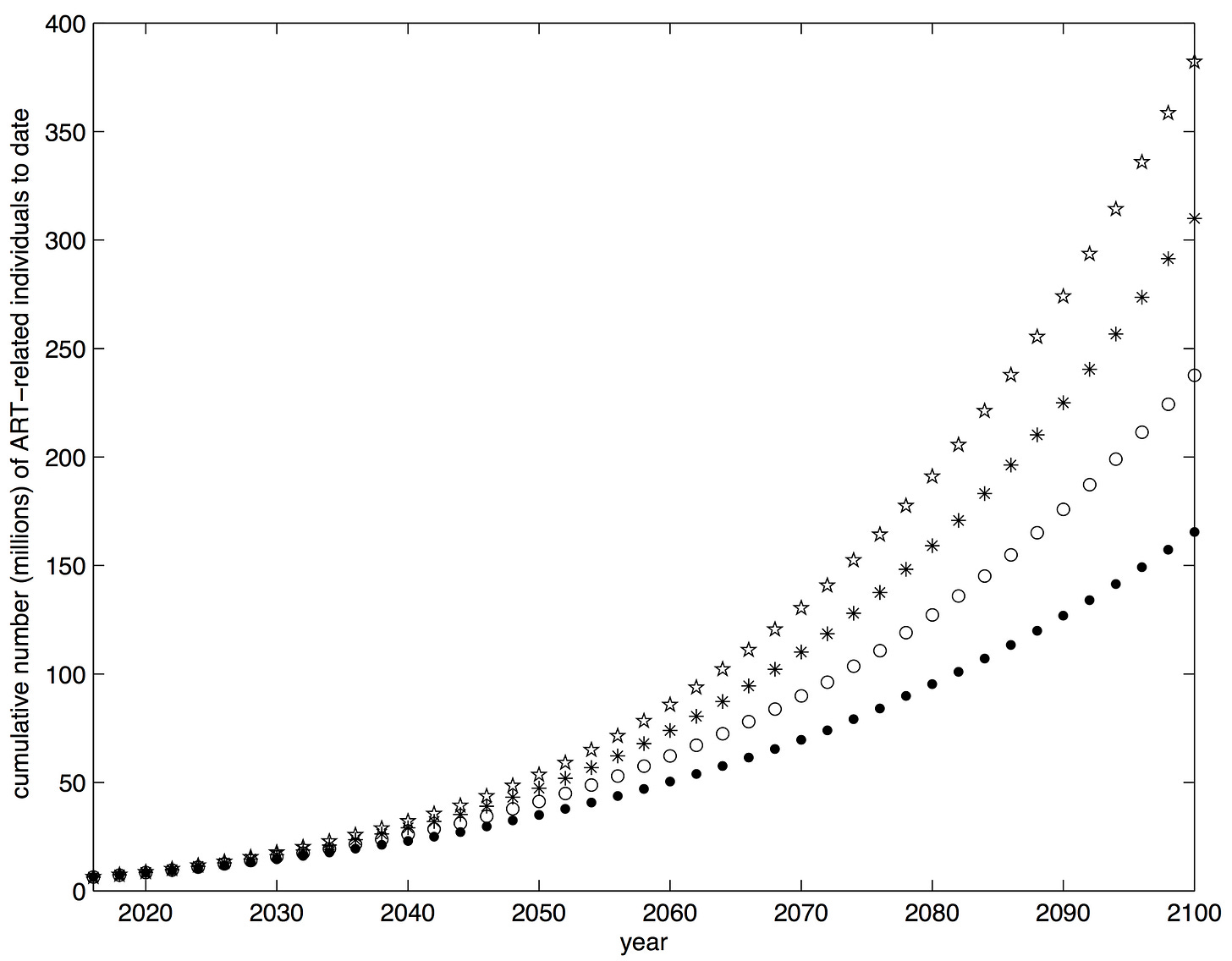

I worked on projections with Malcolm Faddy and my son, Matt, who have the actuarial expertise I lack. Our paper can be read here. It is easy to pick holes in it because reliable data for births and other variables are hard to gather and verify. We rounded up numbers to the nearest thousand and fixed a mean family size (1.8) and maternal age at first birth (30). Variations of age-specific mortality hardly affected results. Fertility services are growing again after pausing in the Covid pandemic, but future growth is almost imponderable. In an unpredictable world, a major war, pandemic, or other catastrophe could upset our conclusions. We therefore estimated the IVF-related subpopulation from four increments of services, ranging from zero to 30,000 extra births per year, to increase the chances of pitching into a ballpark.

At the conservative end of the range, we reckoned there will be 167 million people owing their very existence to IVF, and 157 million still alive in the year 2100. They represented 1.4% of births. That projection is probably too pessimistic, especially if services spread throughout Africa. The uptake by so many young people could fill huge unmet needs, especially for women suffering a social stigma from infertility. In the upper range, 394 million people will exist, or 3.5% of total births. Whether zero, low or high growth is more realistic, the magnitude of additional people surprised us. Think of it compared to the size of the current Russian population at the low end and the United States plus Canada at the high end. We hope others will repeat our tentative attempt to weigh the numerical impact of ARTs when more data is available.

We never make a finer investment than in our children. And yet, infertility was a Cinderella subject for far too long and denied much public funding or even sympathy. The subspecialty is now mature but remains short-changed for research into improving treatment and bringing down costs. Denmark is leading the way by opening general access to services, as an expert described elsewhere in this “Stack.” No one is too poor to receive excellent care. The country’s IVF birth rate approaching 10% of the total is a significant compensation for its baby-bust. The translation of a generous policy beyond other welfare states may seem unlikely, but where humanitarian sympathy for involuntary childlessness is not enough, perhaps a national self-interest in boosting the numbers of youth will prevail. Having babies is a personal choice, so earmarking taxpayer dollars will be tough in America despite a reproductive rate of 1.78, causing demographic anxiety. But after the ironies, here is an ultimate paradox. After IVF came under attack early in this election year, Donald Trump presented himself as the godfather of IVF. He even promised government and insurers would pay for services. Don’t hold your breath.

Illustration: Credit: Neelakshi Singh (Unsplash). Vector graphic courtesy of Freepik

Next Post: The Amazing Doctors Jones

Thank you for this thought provoking piece. I have two concerns:

-There seems to be a risk that subsidising ART could incentivise people to postpone attempting to conceive. Whilst this is not a problem per se, it would straight away reduce the reproductive rate per unit time (in delaying parenthood), and therefore not be as effective at combating ageing population as the completed fertility effects would suggest. More notably, it also seems to me that many people, if they do delay believing that ART has them covered, would end up childlessness who would not otherwise - ART is still not that effective for older prospective parents and people have misinformed impressions of their efficacy. I worry about this unintended consequence.

-If we reach a point where a large number of people owe their lives to ART, and the bulk of these because of infertility, it seems to me that this will massively increase genetic risk factors for biological infertility. This has obvious issues for long run creation of human generation after generation.

Of course, I am sympathetic to infertility struggles that people have and I am not opposed to measures helping them. But I think it is worth considering these effects, so we can think of solutions. E.g., alongside ART subsidies could be information campaigns ensuring that people do not overestimate their effects. E.g., reliable PGS's for fecundity could enable embryo screening to offset the increase in genetic risk of infertility.